By Mike Dolan

LONDON (Reuters) – Even though fears of another “sterling crisis” have been wide of the mark for decades, they are harder to bat away this time around as a fourth British prime minister in six years takes the helm.

In an interview last month, Bank of England chief Andrew Bailey testily dismissed the notion of a UK currency or balance of payments crisis brewing, blaming global U.S. dollar strength for the pound’s 20% plunge against the greenback over the past year to within a whisker of levels not seen since the mid-1980s.

“It is not a crisis in my view at all.”

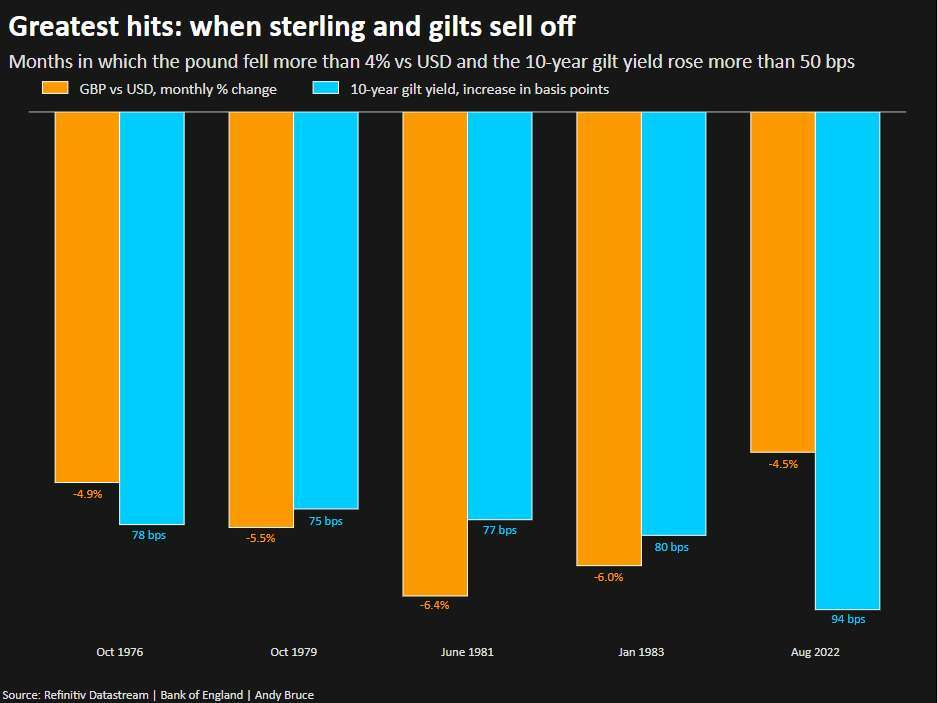

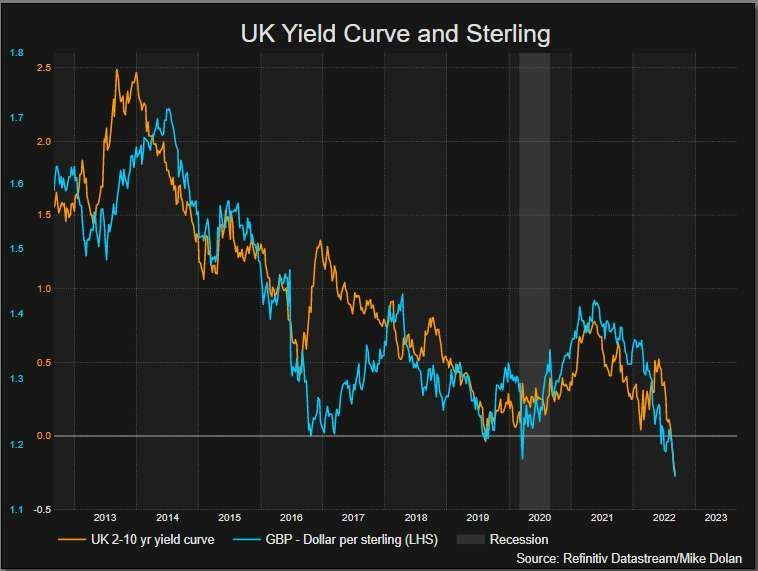

But the rare sight of the pound and UK government bond prices falling in tandem ever since sounds an alarm bell that there’s something more awry than a love for the dollar or the ebb and flow of volatile currency markets.

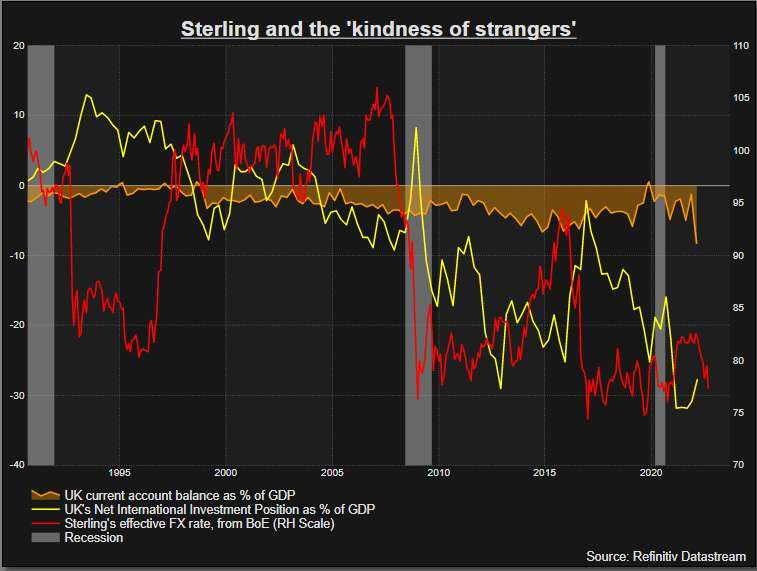

Foreign investors seem to be balking at a toxic mix of surging UK inflation and inflation expectations into a looming recession, with interest rates climbing steeply just as government borrowing is set to soar again under new PM Liz Truss. Moreover, Truss seems intent on cutting taxes even as she indicates more than a 100 billion pounds of additional spending to ease the winter energy price crunch.

With post-Brexit trade policy uncertainties also hanging, overseas financiers seem minded to steer clear of UK assets.

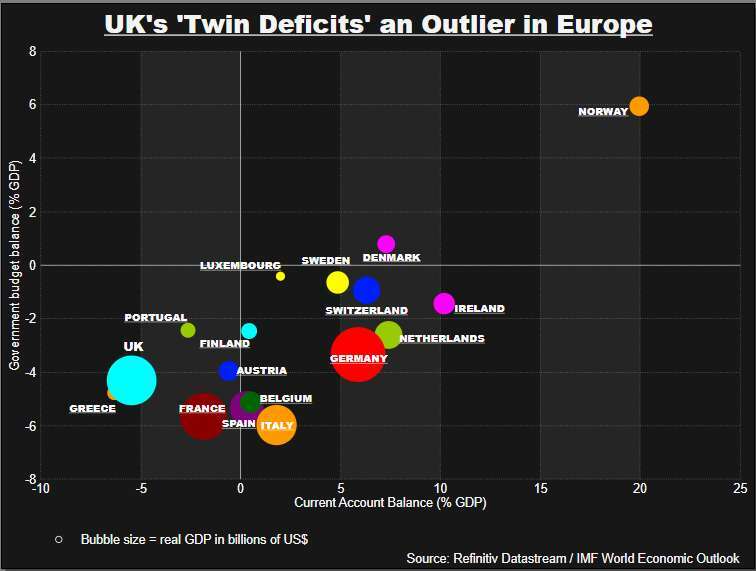

In a headline-grabbing research report this week, Germany’s Deutsche Bank said the risks of a UK balance of payments crisis were rising and foreign investor confidence could not be taken for granted as risk premia on government bonds rose and borrowing became more expensive.

What’s more, it reckoned sterling’s trade-weighted index – down 7% since January – may need to fall another 15% to drag the country’s record current account deficit of more than 8% of national output even back to 10-year averages.

“If investor confidence erodes further, this dynamic could become a self-fulfilling balance of payments crisis whereby foreigners would refuse to fund the UK external deficit.”

The very phrase “sterling crisis” resonates deeply with many in Britain as it conjures up some of the darkest moments of post-World War Two UK economic history – when the country struggled to retain the confidence of foreign investors needed to finance its chronic balance of payments deficits.

As these periodic crises – 1967, 1976 and 1992 – tended to happen during periods of fixed or semi-fixed exchange rates, resolution often meant deep currency devaluation to make UK assets sufficiently cheap and draw back foreign capital.

The first two at least also needed conditional bailout loans from the International Monetary Fund to help steady the ship and prop up the pound at new rates that would allow government to borrow again at affordable rates in the bond market.

But as sterling has floated freely since 1992’s ejection from Europe’s exchange rate mechanism and as the Bank of England has resorted to money printing and bond buying to support government borrowing over the past 15 years, the very idea of a classic sterling crisis and foreign funding crunch dissipated.

Sure, the pound has swooned at times – but the absence of inflation for the past two decades allowed the BoE to underwrite the gilt market in times of emergency government borrowing loads and the lower exchange rate drew foreign capital back quickly to recapture equilibrium and gave exports a lift into the bargain.

Greatest hits: when sterling and gilts sell off https://fingfx.thomsonreuters.com/gfx/polling/gdpzyxwxrvw/Pasted%20image%201662474758002.png

UK Twin Deficit outlier https://fingfx.thomsonreuters.com/gfx/mkt/klvykazabvg/One.PNG

UK current account and sterling https://fingfx.thomsonreuters.com/gfx/mkt/dwpkrxaxqvm/Two.PNG

SUMMER OF ’76

Times have changed. Now the resurgence of inflation, rising interest rates and active Bank of England bond sales to reduce its balance sheet all change the equation just as the need for foreign money rises ever higher as trade and current account gaps balloon.

Deutsche fretted about the similarities with the 1976 sterling crisis – which was also seeded by an energy shock, aggressive fiscal spending and sterling weakness and led to a painful IMF bailout. And it said the new prime minister must convince investors she can find the right balance because “expansive, poorly targeted fiscal policy would widen twin deficits and worsen inflation expectations”.

If overseas money dries up, the Bank of England could resort to bond buying again – but this would cut across its inflation fight and stated plans and potentially raise inflation expectations and borrowing premia further.

Overseas funds acknowledge sterling may already appear relative cheap on fair value models but they can’t yet see a way around the multiple domestic problems.

Cesar Perez Ruiz, Chief Investment Officer at Pictet Wealth Management, said he was still “very negative” on gilts and on the pound despite valuations. “A lot of people are looking at the UK as if it were an emerging market,” he said. “And in that scenario the victim tends to be the currency.”

Nomura’s strategist Jordan Rochester also reckons it’s best to stay short of the pound because the government’s 100 billion pound spending plans to cap household energy bills, unlike similar pandemic supports two years ago, would see UK balance of payments and terms of trade deteriorate even more while debt costs surge.

For HSBC strategist Dominic Bunning the risk for sterling remained to the downside beyond fleeting rebounds.

“The UK may have a new Prime Minister, but the economy and the currency face the same old challenges: weakening growth and high inflation, widening external imbalances and a reliance on foreign financial inflows.”

Sterling and the UK yield curve https://fingfx.thomsonreuters.com/gfx/mkt/zjvqkrermvx/Three.PNG

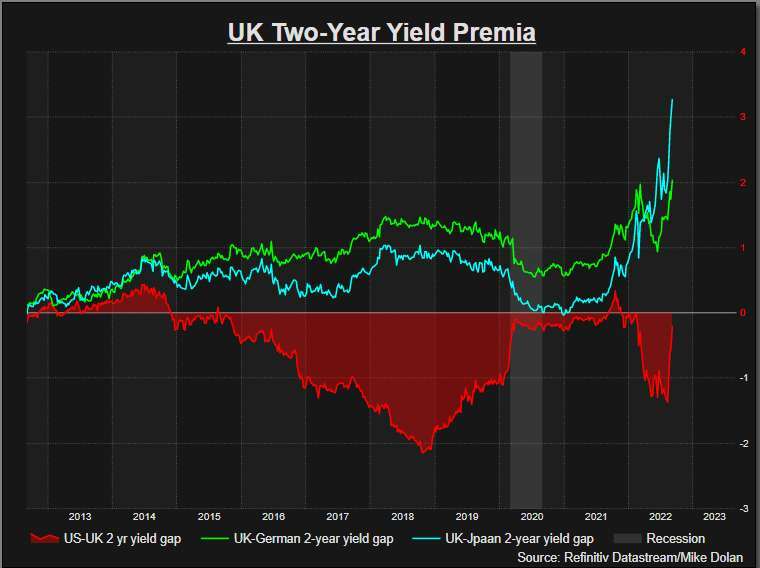

UK 2-yr Yield Premia https://fingfx.thomsonreuters.com/gfx/mkt/xmvjoalaxpr/Four.PNG

The opinions expressed here are those of the author, a columnist for Reuters

(by Mike Dolan, Twitter: @reutersMikeD; Added chart from Andy Bruce; editing by David Evans)